|

|

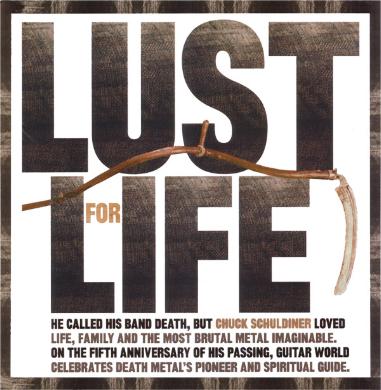

| IT WAS EARLY 2001 when Chuck Schuldiner’s headaches returned. Over the past year, he had begun to feel like his old self again—remarkable, considering that, just one year before, the death metal guitarist had nearly died. In early January 2000, doctors in New York City had labored to remove more than half of a cancerous tumor nesting at the base of his brain. Months of physical therapy followed while he recovered at home, in Altamonte Springs, Florida. Chuck had never liked being far from the Orlando suburb, where he’d grown up with his sister Beth and brother Frank. This was where he thrived, where he drew inspiration for the melodies that tempered the jagged shards of music he had crafted for Death, the band with which he pioneered the ferociously manic sounds of the death metal genre in the mid Eighties. And indeed, in the months after his surgery, Chuck had begun to craft a fresh batch of songs for his new group, Control Denied. “We spent the summer of 2000 rehearsing and recording demos of the new songs,” recalls Richard Christy. “It was fun, and Chuck was doing really well.” Familiar to many as a cast member of the Howard Stern Show since 2004, Christy is also a professional drummer who is best known for his work with Iced Earth, Death and Control Denied. At the time of the 2000 recording sessions, Christy had known Chuck for only a few years, but the two men were as close as brothers. “We were both passionate about metal, and we loved to go to the same bars in Orlando and hang out. “But basically what it came down to was that we made each other laugh. We would do prank calls together in the middle of practice. And he had this dog that would make this weird face when it was happy, and snort like a pig. So when me and Chuck were happy, we’d snort like pigs.” As the end of 2000 approached, there was much to be happy about. Chuck was strong and back at work on his music. His new songs sounded great and continued to build upon the technical and progressive metal of Control Denied’s 1999 debut, The Fragile Art of Existence. “And then we went into the studio,” recalls Christy. “And his health problems started coming back.” For the next 11 months, Chuck battled against his deteriorating health, trying to win time to work on his music. On good days, and often on bad, he could be found writing new songs, or entrenched in the studio, still at work on the album. “He drove himself unmercifully that last year,” says his mother, Jane Schuldiner. “We worried so much about him and begged him to rest. As the perfectionist he is, he said it was just okay and that wasn’t good enough for him or his fans. He would go on until he couldn’t anymore.” “Music was Chuck’s focus. It was the thing that gave him strength,” says Christy. “It was inspiring to see somebody going through something so hard and still playing guitar and writing music. Chuck was just so committed. He gave it everything he had.” *****

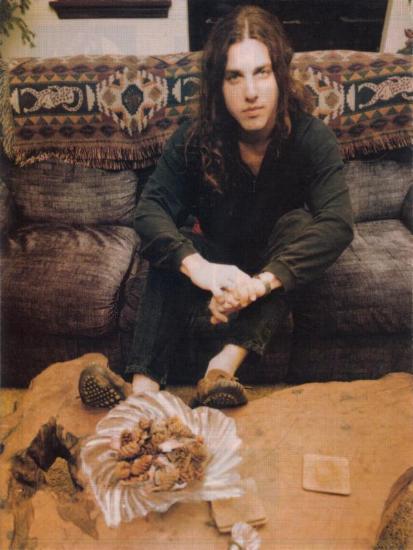

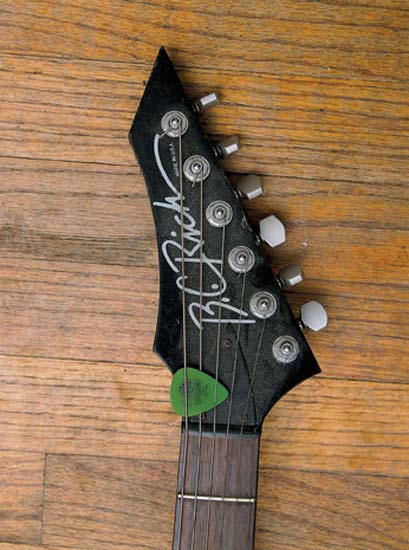

NAMING YOUR BAND “Death” is either tongue-in-cheek insolence or a demonstration of unadulterated sincerity, and Chuck Schuldiner was not given to flippancy where his music was concerned. Next to his family, music was most important to him, and this clarity drove him. To call his band Death was to equate his life’s purpose with that most unimaginable fate: it was predestined and non-negotiable. With Death, Chuck affirmed his life. That he found his way there at all seems prophetic. When Chuck began making music, death metal didn’t exist as a genre but as a virile, yet negligible, strain of heavy metal practiced most evidently by Britain’s Venom. Low tunings, guttural vocals and extreme speed were the musical ingredients, topped off by lyrical praises of the devil, hell and inglorious black deeds. By the time Chuck appeared with his first group, Mantas, in 1983, scattered pockets of growling dark lords were plying their brand of metal in parts of the U.S., chiefly in Tampa and Orlando, the Bay area and Chicago. Chuck came to this music with a goal “to bash out the most brutal riffs ever, with the most brutal guitar sound ever,” he told Guitar School, but almost immediately, he set his sights higher. “Though things were very crude back then, I still had a vision of becoming a very musical death metal band.” The vision was everything. It pushed Chuck to create Death, in 1984, and through Death he came to define at last the genre of metal infesting the underground. The release of Death’s full-length debut, Scream Bloody Gore, in 1986, gave the scene a united front and furthered the awareness of death metal as a genre. Although the music’s standards had long been established, Chuck raised the bar with his technical and melodic riffing, while he upped the horror quotient with lyrics that drew colorfully from gore movies like Make Them Die Slowly and Re-Animator. The death metal scene grew, and as the audience for established acts grew, a host of new bands emerged, each trying to out shock its predecessor. By the early Nineties, the scene was overpopulated by speed-riffing Satan-worshipping metalheads. “Death metal has now become exclusively about being evil, Satanic and playing full speed ahead,” Chuck complained to U.K.’s Metal Forces in 1991. “It’s not what I’m into at all.” By then, Chuck had tackled topical subject matter that included abortion (“Altering the Future”), the struggles of the terminally ill (“Suicide Machine”) and the right to die (“Pull the Plug”). Committed to his vision, Chuck gave shape to death metal, then took it to new heights. But it was not without its costs. His demands of himself and his band mates occasionally led to acrimonious breakups. Business dealings left him feeling overwhelmed and depressed: “The biggest frustration with the music business for Chuck were the labels,” says Jane Schuldiner. “He told me that if he could bypass the labels and just play for the fans, he would be a happy man.” And in the spirit of all pioneers, Chuck could be recklessly impulsive, as when he pulled out of a European tour just days before it was to begin. But humility tempered his character. “He was always surprised when people would come up and say they were such a huge fan,” says Christy. “He was the most humble guy. I don’t know if he ever realized how important he was to the metal scene, because he looked at himself as a fan of it.” And so it was, in 2000, during Chuck’s brief recovery, that he and Christy were attending a King Diamond show in St. Petersburg, Florida. The corpse-painted thrash metal singer was a favorite of Chuck’s, and Diamond’s guitarist, Andy LaRocque, had even briefly performed with Death, on 1993’s Individual Thought Patterns. With LaRocque’s assistance, Chuck and Christy were escorted backstage. “I just remember us being so nervous to meet King. Chuck was in awe,” says Christy. “And for me, it was just so weird: there I was, a Chuck Schuldiner fan since I don’t know when, and I’m watching him get tongue tied in front of his hero. But Chuck was just like any other metal fan. That’s what made him and his music so great.” ***** HE WAS BORN Charles Schuldiner on May 13, 1967, in Long Island, New York, the youngest of three children born to Malcolm and Jane Schuldiner. Malcolm was a Jew of Austrian decent; Jane was born and raised in the bible belt South. Rearing their children, the couple exposed them to the practices and customs of both faiths, “including the holidays,” says Jane. “They ended up being the best of both.” When Chuck was one, his parents moved their brood to the budding suburb of Altamonte Springs. Jane calls Chuck’s childhood “a Leave It to Beaver life.” Altamonte Springs was largely undeveloped at the time, and the Schuldiner home was nestled in forests where Seminole Indians once hunted. “Chuck and his brother and sister grew up playing in those woods, building forts in the trees and seeing quite a lot of wildlife there also,” says Jane. “Chuck and Frank camped out in the backyard with flashlights and snacks lots of times, and there were many of the children in the neighborhood at the house most days.” Chuck’s childhood was, by all accounts, happy and traditional. Family photos from the time give some clues to his preteen interests: young Chuck dressed up as an Indian scout, displaying the catch from a fishing trip and posing in his soccer outfit. His artistic streak displayed itself early. Says Jane, “Chuck was interested in art and sculpture from a young age and loved both equally.” Although Frank was seven years older than Chuck, the two were close companions. One day, while returning home from a visit to an out-of-state uncle, Frank was killed in a car accident. He was 16. His death was devastating for Chuck, and the sobering reality of the loss haunted him. “He never really came to terms with it,” says Jane. “He always missed Frank.” In the months after Frank’s death, Malcolm and Jane looked for ways to help Chuck deal with his grief. He had begun to take an interest in music, and the guitar had aroused his curiosity. “We discussed it with him, and an acoustic guitar seemed the best,” says Jane. “It was portable, something he could carry with him when we went on vacation or camping, to a friend’s house or wherever.” Chuck signed up for classical guitar lessons, but the tedium of study quickly wore down his enthusiasm. “I took two lessons, and [the instructor] showed me ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb,’ ” Chuck recalled to Pit magazine’s Brook Everitt in 1999. “I said screw it and went on my own.” “Chuck found the acoustic guitar lessons and his teacher boring,” says Jane. “He didn’t like the repetitiveness of it all.” It’s possible that Chuck would have abandoned the guitar entirely had his parents not made yet another attempt to indulge his interest. While at a yard sale, Chuck spotted an electric guitar, a pointy knockoff in the spirit of B.C. Rich, whose instruments he would later use extensively. Once the guitar was in Chuck’s hands, his old acoustic was forgotten. “The first time he played the electric guitar, it was as if a switch was turned on in him,” says Jane. “And it never turned off.” His enthusiasm was in large part fueled by his love of Kiss, who by this time in the late Seventies had reached their commercial zenith. For years, they were Chuck’s favorite group, as evidenced by a family photo in which a very young Chuck is dressed up like Paul Stanley. At the age of 13, he was treated to his first Kiss concert, courtesy of his mother. By then, he had discovered metal through New Wave of British Heavy Metal acts, including Raven and, his favorite, Iron Maiden, whose guitar tandem of Dave Murray and Adrian Smith were critical to forming his love of heavy, but melodic, guitar lines. In lieu of guitar lessons, Chuck had begun to teach himself to play by ear, listening to his favorite songs and, with uncommon determination for an adolescent, sounding them out on the fretboard of his guitar. “He had a very good ear for music early on, and what he listened to he taught himself to play,” says his mother. “He absolutely loved doing that.” In the metal-intensive years of the early Eighties, Chuck found no shortage of fresh inspiration. In addition to U.S. bands like Van Halen, he was captivated by Scandinavian metal acts such as Hellhammer and Mercyful Fate, and Britain’s Venom, who would inform his growing death metal sensibilities. In 1983, the arrival of thrash acts like Metallica, Possessed and Slayer introduced him to music heavier and more brutal than anything he heard before. By then, he was 16 and coming into his own as a guitarist. “I was lucky to start playing guitar in the Eighties,” he told Pit, “when so many great players were around to inspire me, like Yngwie Malmsteen, Van Halen and especially Dave Murray and Adrian Smith of Iron Maiden.” Chuck’s growing fondness for extreme metal was no cause for alarm around the Schuldiner household. Malcolm and Jane had always been supportive of their children’s interests, and Frank’s death only brought the family closer. “There is always fear involved when a child dies, and I watched diligently, afraid it could happen again,” says Jane. “Chuck’s father worked and had tennis and other hobbies, so I was more involved with Chuck and his interests, as I was with my other children.” And so when Chuck decided to form a band with two local high schoolers, the garage was given up to the group’s rehearsals. They called themselves Mantas, a pseudonym first adopted by Venom guitarist Jeffrey Dunn. Chuck’s cohorts in this venture were guitarist Frederick DeLillo, rechristened Rick Rozz, and drummer/ singer Barney “Kam” Lee. The band had no bassist. Chuck wrote most of the band’s material and occasionally shared vocal duties with Lee. Shortly after forming, Mantas released a five-track cassette called Death by Metal, recorded in Schuldiner’s garage. Its cover photo featured the three band members in front of a sign that reads “Danger High Voltage.” Public reception to the group was anything but electric, however. That, combined with internal band tensions, led to Mantas’ breakup in late 1984. For the first of many times to come, Chuck found himself searching for new band members. Not surprisingly, given the uncommon nature of his music, he found his options limited. Within weeks of Mantas’ breakup, Chuck had reconciled with Rozz and Lee. The old lineup reconvened but with a new lead singer—Chuck—and a new name: Death. It was the definitive name for what would become one of the genre’s defining bands. But for Chuck’s mother, the name rubbed against the still fresh wounds of Frank’s untimely death. “I always thought that the name of the band derived from the death of his brother,” says Jane. “And while the word had such painful memories, I did not object.” Under Chuck’s leadership, Death began to find their distinctive voice. As both the writer and singer of their lyrics, he turned the focus away from Lee’s devil imagery, toward gore. The group released the five-song cassette Reign of Terror in October 1984, and the three-track Infernal Death tape in March 1985. Both were praised and traded in the underground cassette market, but the trio broke up again soon after Infernal Death’s release. While Lee and Rozz joined Massacre, a local death metal act that had formed the previous year, Chuck weighed his options. By now, he was nearly 18 and close to graduating high school. Though he’d been a good student, Chuck was bored by school and anxious to pursue a record label contract. As always, he turned to Malcolm and Jane for guidance. “We talked with his school counselor, who urged us to let Chuck pursue his dream,” says Jane. “Which we did after getting his promise that if, after a year, he did not get that contract, he would finish school and go to college.” Though he had only a handful of independent cassette releases to his credit, Chuck clearly felt ready for a professional career. He’d been practicing at every possible opportunity, and on increasingly better instruments. At some point in the early Eighties, Chuck switched from his yard-sale electric to a Peavey T25, a two-humbucker model manufactured in 1982 and 1983. A photo from this time shows him posing with the guitar, a young teen practicing his attitude for the camera. Eventually, he would move on to a B.C. Rich Mockingbird before choosing the B.C. Rich Stealth model, a rarity offered through the company’s Custom Shop. This became his main guitar throughout most of his professional career. ***** CHUCK’S FIRST ACT as an emancipated musician was to head for San Francisco and its burgeoning pool of metal musicians. His search was unsuccessful, but in January 1986, shortly after returning home, he was invited to join the Canadian thrash act Slaughter. He accepted and moved to Toronto but left two weeks after arriving, having recorded just one track with the band. By now it was clear to Chuck that he had to follow his own musical goals. “Of course, his father and I were involved the first year, from afar mostly,” says Jane. “After that, Chuck discussed his plans, but his decisions were always his own. We trusted him to do what was best for the band, with the inferred promise that it would, above all, be the best for himself, also.” That March, back in San Francisco, he met drummer Chris Reifert and struck up a friendship. The following month, the duo entered a Bay Area studio to record the three-song demo Mutilation, with Chuck doubling on bass. Mutilation was by far the most professional sounding of Death’s demos, and like its predecessors, it was circulated through the underground tape-trading circuit. Which is how writer Don Kaye first came to hear it. “I was big into trading tapes on the underground scene, and I had been aware of Chuck’s music since the first Mantas tape was released. The Mantas tape was pretty primitive, but right from the start with Chuck, you could tell that he had talent on the guitar and with writing pretty catchy stuff within that genre. There were so many bands coming out of that scene, but as always, the problem was that they were trying to be as heavy and brutal as possible and weren’t able to write anything that sounded like a reasonably coherent song. Chuck was good, and he just got better as he moved closer to making the first Death album.” At the time, Kaye was dividing his time as a journalist for metal magazines, including Kerrang! and working part time as a publicist for Combat Records in New York City. The heavy metal record label had formed in 1984 and quickly found success when it signed Megadeth and released their 1985 debut, Killing Is My Business…And Business Is Good. Aware that Death had a good buzz on the underground scene, Kaye urged Combat’s chief, Steve Sinclair, to sign them. “I said, ‘They’d be perfect for the label. They’re definitely a band that’s getting a lot of attention from people.’ He was very hesitant, but I just kept badgering him to do it, until, finally, he agreed.” That summer, following

an abortive attempt to record their debut in Florida, Chuck and

Reifert nailed down a dozen tracks in five days at the Music Grinder

in L.A. The band, such as it was, still didn’t have a bassist,

and Chuck once again handled four-string duties. Titled Scream

Bloody Gore, Death’s debut was released upon an unsuspecting

public in May 1987. Its songs were little more than an extension

of the piledriving riffs and blood-and-gore lyrics that had populated

Death’s demos. But the professional production, coupled

with Combat’s extensive distribution capabilities, allowed

Scream Bloody Gore to have an impact that Death’s

homebrewed releases never could achieve. |

continued “But Steve was a ball breaker. And sure enough, when we got copies of the album in the office, right there on the inside sleeve, under the lyrics and credits, it said, ‘This record is Don Kaye’s folly.’ I just thought, Oh god.” Kaye’s reaction was nothing compared to Chuck’s. “Now Chuck was a guy who was very passionate and very serious about what he did, and he could be a little bit abrasive,” recalls Kaye. “But he saw this, and he called me, and he was just livid. He said, ‘Who’s gonna take this record seriously when it says it’s somebody’s folly?’ He was really pissed off. “But it showed me that, although sometimes to his detriment, Chuck took his music really seriously. He was really interested in death metal and going as far as he could with that.” Any animosity Chuck felt was short lived. “Death certainly had a good run with Combat. They did five records with them.” Two years of traveling between coasts had convinced Chuck to make his home in Florida, near Altamonte Springs. His family welcomed the decision. “Chuck moved out on his own to a town near us and saw us when he wasn’t touring, inviting us over for dinner and visiting us often,” says Jane. Chuck had invited Reifert to return to Florida with him, but the drummer declined, preferring to stay in California. Once resettled in Florida, Chuck went about creating a new Death lineup, a process complicated by his demanding standards. Henceforth, he would be the group’s only consistent member. “I think he was a perfectionist,” says Kaye. “He really had a high standard and maybe that made it harder for some people to work with him and meet those demands. And as the band went on, the music just got more complex. It was easy to play that kind of music poorly, but it was very hard to keep up with someone like Chuck.” For Leprosy, Death’s 1988 follow-up, Chuck turned for studio support to Massacre, the death metal band Rick Rozz and Kam Lee had joined in 1985. By this time, Lee had left the group, replaced by Bill Andrews. With Massacre bassist Terry Butler onboard, Chuck was freed from four-string duties. Recording was, by various accounts, a happy experience. Chuck’s old friends proved they were up to his standards, and Leprosy’s polished production put their contributions to good display. Musically, Chuck was continuing to grow, his philosophical side emerging in “Pull the Plug,” a song about life support and the right to die. The group reconvened for 1990’s Spiritual Healing, with virtuoso metal guitarist James Murphy replacing Rozz. The album marked a breakthrough in Chuck’s music and lyrics. Turning his attention to the daily headlines, he found everyday America a place of tune-worthy horrors. “Living Monstrosity” spoke to the crack epidemic and the drug’s affect on unborn fetuses, while “Altering the Future” laid out what he saw as the implications of abortion. With their focus on real-life problems, the new songs seemed more morbid and pessimistic than Chuck’s previous songs. But he wasn’t indifferently mining grief for artistic inspiration; he believed in what he sang. He was, says Jane, a “deep thinker, a ponderer, and his lyrics came from his feelings about life happenings… and things he felt was wrong in the world. He was a very concerned person for the wronged people in this world, and it saddened him.” Musically, the album showed Chuck continuing to grow as a songwriter and guitarist. “I started practicing more and came up with the idea that, for this band to move forward musically, we’d need a cleaner approach, something real dry and in your face,” he told Guitar magazine. At a time when death metal was in danger of becoming a grunting, Satan-glorifying parody of itself, Spiritual Healing showed that death metal was important and that Chuck Schuldiner was undeniably the person to show the way forward. Ironically, Chuck had been cast out of his own band. In the weeks after the album’s completion, personal and business problems had begun to overwhelm him, and Chuck pulled out of the European tour that had been lined up. “I came to a point [at] which I thought everything was doomed to fail,” he told Arno Polster, without elaborating on the details, in the March 1991 edition of Germany’s Rock Hard magazine. To Chuck’s surprise, his band members decided to go without him. It was an unforgivable mutiny, made worse by their denunciations of Chuck onstage and in the media. Butler told Rock Hard that Chuck was home, mowing the grass. In response to their actions, Chuck hired an attorney and gained the rights to the name Death. “After all, Death is still my band,” he told Polster. “I thought they were my best friends, but I was wrong. At all times, musicians are replaceable. Friends are not.” Chuck had never needed an excuse to fight for his music. Now handed one, he responded with devastating force. Human, his follow-up to Spiritual Healing, was a calculated retaliation against his former bandmates, who claimed he was washed up, and the metal media, which painted him as a narcissistic monster. “This is much more than a record to me,” he told Metal Hammer’s Robert Heeg in the December 1991 issue. “It is a statement. It’s revenge.” Shedding the gory trappings of his past lyrics, Chuck now wrote in a manner that seemed wholly introspective and personal. It’s not hard to imagine him addressing Butler in “Secret Face,” where he sings of “a mask / That covers up one’s true intentions,” or in the opening lines of “Lack of Comprehension”: “A condemning fear strikes down / Things they cannot understand / An excuse to cover up weaknesses that lie within / Lies.” Certainly, the intricacy and nuance of Chuck’s songwriting make it clear he had not spent the past year lying around. He had been striving to give Death a more technical sound, and on Human he succeeded, in part due to his choice of musicians. Guitarist Paul Masvidal and drummer Sean Reinert were recruited from Florida technical hardcore band Cynic, while bassist Steve DiGiorgio came from California’s highly technical thrash band Sadus. Chuck’s musical growth continued with Death’s next two albums, Individual Thought Patterns and Symbolic, but as the Nineties wore on, he was beginning to tire of his role as guitarist and frontman. As early as 1993, he had told Guitar School, “In the future I plan to do a more melodic, straightforward metal side project with a singer in the Rob Halford style.” By 1997, he was ready to take action. Placing Death on hiatus, Chuck began to lay the plans for his next musical project, Control Denied. “Chuck wanted to have a band in which he did no singing, that was the main reason,” says Jane. “Singing was really hard on his voice.” Adds Richard Christy, “He just wanted to try something with a more traditional metal singer, because he was a huge fan of bands like Iron Maiden, Manowar and bands like that. I don’t think he ever wanted to stop doing Death full time, because he knew how much that band meant to people. But he was ready for a break.” Christy was among the first people Chuck selected for Control Denied. They had met by chance in 1996: The drummer had just moved to Orlando with his band, Burning Inside, and was shopping at Altamonte Mall with his guitarist when they spotted Chuck at a B. Dalton bookstore. “We walked in to check out some metal magazines, and there’s Chuck reading a magazine! And we were like, Oh, should we say hi? So we said hi, and he was super nice. We told him we were huge fans, and—I’ll never forget this—he took the time to talk to us. We talked to him for, like, 15 or 20 minutes about metal, and it was just so cool. We couldn’t believe that in a mall in Orlando, Florida, we were meeting Chuck Schuldiner.” Soon after, Christy and Chuck began bumping into one another. “Pretty much everybody in the metal scene in Orlando would hang out at the same places,” says Christy, “the same shows, the same parties.” By coincidence, when Chuck was in need of a drummer for Control Denied, a mutual friend suggested Christy. “They got me in contact with Chuck, and I was so nervous just calling him to set up an audition. I remember taking my drums to Chuck’s rehearsal space and playing four of the most complicated Death songs right in a row, without stopping or any mistakes. Right then, it just clicked. It just felt awesome, because I had been playing along to those songs on CD for years. And to be there playing them with Chuck was mind blowing.” Christy got the job and, with it, a little surprise: though Chuck was ready to move ahead with Control Denied, he decided to accommodate his new label, Nuclear Blast, with one more Death album. “I was super excited about that because I was a huge Death fan,” says Christy. With Scott Clendenin on bass and Shannon Hamm on guitar, Chuck began recording The Sound of Perseverance, Death’s most aggressive, progressive and technically challenging album. Opening with the savage blast of “Scavenger of Human Sorrow,” the album was relentless in its fury and musical virtuosity, culminating in a blistering cover of Judas Priest’s “Painkiller.” Released in 1998, The Sound of Perseverance was Death’s seventh album and, in the opinion of many fans, their best. Christy recalls the subsequent tour as a happy time. “In Italy, our bus pulled up to this club in Milan, and there were hundreds of kids waiting there. We got out and headed to a restaurant, and these kids started following us down the street, like it was a parade, and chanting Chuck’s name. We get to the restaurant and start eating, and all those kids had their faces pressed against the windows, watching us eat. It was like a zombie movie! Chuck got such a kick out of that. He was so humbled, too.” *****

WITH THE Sound of Perseverance tour completed, Chuck and his new group went to work on Control Denied’s debut in early 1999. The sessions were well underway that May when Chuck began to experience pain in his upper neck, which he believed was caused by a pinched nerve, possibly from strain. An MRI scan proved he was right about the pinched nerve; unfortunately, it was caused by a tumor growing at the base of his brain. On May 13, his 32nd birthday, Chuck was diagnosed with pontine glioma, a rare type of brain stem cancer that typically affects children. Says Jane, “Chuck’s doctors determined that he had that tumor from childhood, with no symptoms at all to alert us through the years.” The tumor’s sensitive location made it inoperable, and Chuck underwent radiation therapy to control its growth. Alternative treatments were sought as well. Because he had no medical insurance—a common situation for many musicians, even those signed to label contracts— Chuck’s treatment was paid entirely out of pocket. In all, his family spent some $90,000 for his therapies. During that time, Beth put her real estate career on hold to take care of Chuck and raise funds for his treatment. “I told Chuck as a joke, ‘You are a full-time job,’ ” Beth told MTV. “Every single dime has been for him, but Chuck would do it for me 1,000 times over.” November brought the release of Control Denied’s debut, The Fragile Art of Existence. By then, fans knew of Chuck’s condition. Many assumed the band’s name and album’s title were references to his illness, but both were chosen before his problems manifested themselves. In the first days of 2000, Chuck and his family learned of an experimental surgical procedure that could treat his condition. Within just one week, they managed to assemble a team of five medical specialists to perform the surgery, and to do so quickly: the head surgeon declared that Chuck’s life was “in imminent danger” and scheduled his surgery for January 19. Although the procedure was expensive, the doctors had agreed to waive their fees. Unfortunately, the hospital hosting the operation, New York University Medical Center, would not waive its fee, estimated at $70,000 to $100,000. Although the center was willing to accept as little as $5,000 as a down payment, Beth was also asked to sign over Chuck’s future royalties to pay the balance. She refused. Still, the surgery went ahead as planned. Nearly half the tumor was removed, and Chuck’s life had been saved. Soon after, he began physical therapy to help him recover from the effects of the tumor and surgery. Within two months, he was telling MTV News, “Everything looks good. I’m moving pretty quick through physical therapy, and we’re seeing good results.” Chuck said he was especially buoyed by the financial donations from his fans and from fellow musicians who put together benefit shows. “When this sort of stuff happens, it really brings people together. It’s incredible how people aggressively organized for this. It’s very uplifting.” Chuck had good reasons to be optimistic. Though the tumor had not been entirely removed, it had reportedly necrotized; the tissue was effectively dead. In addition, if the tumor had been with Chuck since childhood, as his doctors said, then it was most likely a low-grade glioma, which is slower to grow and less aggressive than a high-grade variety. In any case, Chuck’s prognosis for recovery looked good. Work went ahead on a new Control Denied album, tentatively titled When Man and Machine Collide. But when Chuck’s symptoms recurred in early 2001, his worst fears were realized . The tumor had returned with a devastating vengeance, invading areas of the brain too sensitive for surgery. “Chuck lived on his own until early in 2001,” says Jane, “when I went to his house to stay with him during the day and eventually full time.” By May, his doctors believed surgery was possible and should be performed immediately. Once again, bureaucracy blocked the door to Chuck’s recovery. Though he had obtained medical insurance since his first operation, his insurer refused to pay for the second surgery—estimated at $70,000 to $120,000—because the tumor existed before the start of his coverage. The Schuldiners, having exhausted their funds on his previous treatments, did not have the $30,000 down payment required for his surgery. Responding to Chuck’s dire condition, numerous artists—including Pantera, Disturbed, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Marilyn Manson, Korn and Slipknot—donated merchandise for an online auction to raise funds. Chimaira solicited donations while on the road, and benefit concerts were organized by metal acts worldwide. The outpouring of support was enormous. Throughout Chuck’s illness, Christy visited regularly, doing his best to keep his friend’s spirits up. “We’d listen to metal together, make prank calls and goof around. We tried not to think about the bad things and just stay positive and think about music and happier things. We would just talk and reminisce and look forward to going on tour again.” “Chuck was the one who never gave up, who instilled hope and love in those all around him, and he never cursed fate,” says his mother. “After losing Frank, he worried so about what it would do to the three of us—Beth, [his nephew] Christopher and myself—to lose him. I promised him we would do the best we could if he were to lose that fight.” Although Chuck’s condition improved by November, his weakened state left him vulnerable to infections. Late in the month, he contracted pneumonia and was placed in the hospital. He was released on December 13 and returned home. One hour later, at 4 p.m., Chuck’s body gave up. He died as one imagines he would have wanted, at home, surrounded by his family. “At the end,” says Jane, “he thanked me for the golden memories of his childhood.” The fate of the final Control Denied recordings has been a matter of contention since Chuck’s death. Recently, the Schuldiners and Guido Heijnens, owner of the now-defunct Hammerheart Records, to which Control Denied was under contract, entered into a lawsuit, with each side claiming rights to the recordings. Heijnens has previously released some of those tracks, against the family’s wishes, on Zero Tolerance, a two-disc compilation from 2004 that also featured Death demos and live recordings. Says Jane, “The legal battle continues with hope that all with be finalized soon. I can tell you that, absolutely, Chuck’s last album will be released exactly as he told his sister and I he wanted it to be done. That was Beth’s last promise to Chuck, and she will keep it.” It’s not putting too fine a point on things to say the fight for Chuck’s music is the fight for his soul. He lived for his music, and he died for it. Clearly, had he chosen a more lucrative occupation or sold out to play a more popular style of music, Chuck might have had the financial means and benefits to beat his disease. But selling out was an unknown concept to him; he could do nothing less than follow his heart. Doing so, he demonstrated how an artist lives: on his own terms, without compromise. “With regard to death metal, he contributed a standard of musicianship that people are still aspiring to,” says Don Kaye. “He was a pioneer who tried to take the music in an interesting and progressive direction. And in that way, coming along when he did, he crystallized the genre.” “His music is timeless,” adds Christy. “It still sounds as fresh as it did when it came out. Plus, Chuck’s style on guitar is unmatched: it’s the perfect mix of melody, technicality and brutality. I’m extremely lucky to have been not just part of the band but also a close friend of Chuck’s. He inspired me, and he continues to inspire me, every day.” He is clearly not alone. “I still receive so many emails from Chuck’s fans,” says Jane. “I know from them that Chuck is remembered not only as a great musician but as someone who made, and continues to make, a difference in their lives. He inspires them still.” Not all those fans are adults who grew up with Chuck’s music; many, says Jane, are as young as 11. “Just think: another generation is discovering Chuck’s music. He would be so proud.” |